Is the education gap closing? More Indigenous students finish year 12 than ever before

By Andrea Booth, Jason Thomas

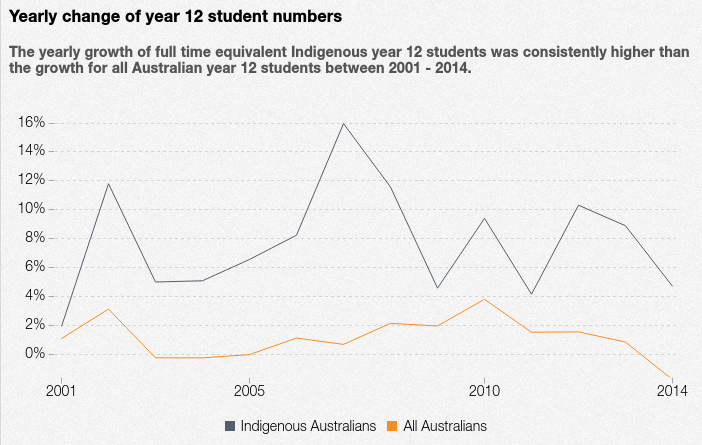

More Indigenous Australians than ever are finishing year 12. What's more, that trend has outpaced the growth of total year 12 student numbers.

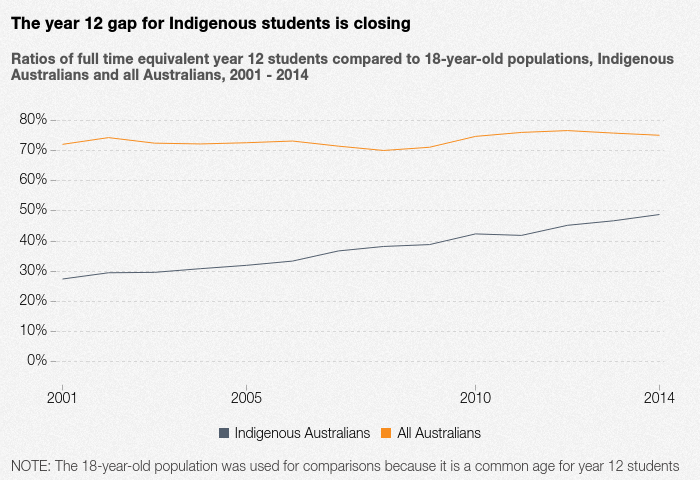

Historically, Indigenous Australians have been less likely than non-Indigenous Australians to make it to the end of secondary school.

But that is changing as the yearly growth in Indigenous year 12 student numbers has consistently beaten the Australian total for the past decade, according to data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics.

That could lead to better opportunities for thousands of Indigenous school leavers each year and for the wider population who identify as First Australians.

People who complete year 12 can generally expect greater career success and employment opportunities, which can benefit whole communities.

I never thought I'd be able to make it to university

Year 12 student from Hope Vale in Queensland, Mitchell Michael, is finishing the last leg of a long race.

Mitchell, who was a boarding captain at Ipswich Grammar School and has travelled interstate for athletics, is now doing what he previously thought was impossible.

"I never thought I'd be able to make it to university," Mitchell said.

Video shows Mitchell Michael talking about Year 12

He compared year 12 to the last sprint of a running race, and said he wanted to keep doing athletics on the side, but looked forward to undertaking a science degree at university.

"At the moment, science is what I like, so that's what I'll stick with."

Mitchell said students who attended university could return to their communities as positive influences.

"You can come back and be a role model to your younger peers, younger kids. They've seen you do it, so they know they can do it."

Another year 12 student, Kalina Luta from Townsville, Queensland, said she planned to study nursing at university and become a midwife.

"My future aspiration is to open my own clinic for Indigenous women to come and give birth," Kalina said.

She agreed with Mitchell that finishing school would set a great example for others.

Video shows Kalina Luta talking about plans to study nursing

"We as young adults and teenagers, what we do, really affects what our younger kids do," Kalina said.

"We're going to become something... we're something."

Kalina, who studied at St Peters Lutheran College, also encouraged other students doing year 12 to persist, despite the challenges.

"At the end of your journey, there's a light and when you get there, you're just so happy because you made your community proud."

Kalina and Mitchell, who received assistance from the Australian Indigenous Education Foundation, said they believed most students at their respective schools would finish year 12.

What is contributing to the growth of Indigenous year 12 students?

One reason for the growth in Indigenous year 12 student numbers is that the population of 18-year-old Indigenous Australians is growing, even faster than the total number of 18-year-olds in Australia.

That means more Indigenous Australians would be in year 12 in 2014 compared to 2001 due to the population growth alone.

But the number of full-time equivalent (FTE) Indigenous year 12 students has grown at a faster rate than the population of Indigenous 18-year-olds.

The number of FTE student numbers is smaller than the actual number of students, since some students study part time.

There are limitations to the ABS data: not all year 12 students are 18 years old, and Indigenous students are more likely to be ungraded secondary (not year 12) than their non-Indigenous year 12 peers, the Australian Centre for Education Research says.

Also, the amalgamated data for Australia does not take into account the differences in outcomes for students in remote and regional locations, compared to their urban-based peers. A change for the legal school-leaving age in Australia's most populous state, NSW, has meant students cannot legally leave school before they are 17 years of age without having employment or being enrolled in other education. While this may be a factor that has contributed to retention in NSW, the growth of Indigenous students in year 12 outpaced the total numbers of year 12 students in years before that.

Australian Indigenous Education Foundation executive director Andrew Penfold did not believe the trend across Australia was due to any one factor.

The latest Closing The Gap report said Australia was on track to meet the target to halve the gap for Indigenous Australians aged 20‑24 in Year 12 attainment or equivalent attainment rates.

The education gap is closing, in some parts of Australia

While these figures may appear positive, it is important to remember that the national data is inconclusive and the gap is not closing in some places, said Dr Peter Gale from the David Unaipon College of Indigenous Education at the University of South Australia.

"The whole focus on closing the gap can be flawed at times if we're looking at amalgamated figures," Dr Gale said.

"If we’re looking at remote Australia, the gap is actually increasing."

"We’re not addressing the disadvantage that's experienced by Indigenous students in rural and remote areas the same way as students from urban areas."

The latest Closing The Gap report also highlighted the difference between remote, rural and urban areas.

"Results vary significantly by remoteness for Indigenous young people, ranging from 65.5 per cent in outer regional areas to 36.8 per cent in very remote areas," the report says.

There are many factors to the disparity in remote areas. One is the expectation that Indigenous students should conduct their school studies in English, while many Indigenous people from remote and rural communities use English as their second language.

Dr Gale said another issue was the cultural barrier for some students from remote locations who may have to go to boarding school in order to finish year 12.

Positive signs in the Kimberley

Broome Senior High School is fostering a high attendance rate of its senior level Indigenous students.

The high school, located in the Kimberley region of West Australia, has a 90 per cent Indigenous retention rate from Year 10 to Year 11. In 2015, 29 Indigenous Year 12 students are set to graduate, the highest number the school has ever seen.

“Rather than leaving half way through Year 11 into meaningless work pathways that fizzle out, the kids have stayed at school, been engaged, finished their Certificate II qualification,” Broome Senior School principal Saeed Amin said in a report he provided to NITV.

Broome Senior School is currently outperforming the national average for Indigenous attendance with a 75 per cent attendance rate, 10 per cent up from the national rate.

This growth has come as student enrolments have increased from 296 in 2005, to 900 in 2015, a 204 per cent increase that has enabled the school to offer the full curriculum to students.

Mr Amin says this compels students to continue through their high school years.

"You don't get Year 12 outcomes unless you get it right in Year 7 onwards," he said.

Mr Amin attributes the school's above-average attendance rate to a culturally appropriate method.

"We've worked hard at understanding the Indigenous lens and how to meet their needs," he said.

"We have certainly moved away from 'this is how the school does it' towards 'if this is what the parents need then this is how we'll do it'."

Staff members have adopted child-progress initiatives such as meeting with parents on their country, instead of requesting they visit school.

Mr Amin also attributes a higher attendance rate to the school's focus on students' potential rather than their immediate performance.

"We need to cross-reference a whole bunch of data and make sure we're not closing doors on kids just because they may have some issue at home, or they haven’t been attending school."

An issue of national importance

Broome Senior High School shows the potential for other remote locations in Australia, but the chances of finishing year 12 for Indigenous Australians is in contrast with higher chances of year 12 attainment for non-Indigenous Australians.

The retention rate for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students to Year 12 completion was 59 percent as of 2014. While this has risen by about 20 per cent over the last 10 years, it is still significantly lower than the rate for non-Indigenous students, which was 84 per cent in the same year.

The Australian Government formed the Close the Gap program in response to the inequality between outcomes for Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians.

But the 2015 report on the policy showed that it was falling behind on all other targets except for two: to halve the gap for Indigenous Australians aged 20-24 in Year 12 or equivalent attainment rates, and to halve the gap in mortality rates for Indigenous children under five within a decade.

Efforts to ensure access to early childhood education for all Indigenous four-year-olds in remote communities by 2013 were unsuccessful.

The goals to close the gap in life expectancy within a generation, halve the gap in reading, writing and numeracy achievements for Indigenous students and to halve the gap in employment outcomes between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians are not on track to be met.

Yet experts continue to stress the importance of schooling for brighter futures.

Australian Indigenous Education Foundation's Andrew Penfold said Australians who have year 12 qualifications are more likely to be employed, pursue higher education, and earn higher incomes than Australians who do not complete year 12.

"Year 12 completion is important. ABS figures show that it’s a reliable predictor of future career success for all Australians," Mr Penfold said.

Research from overseas also suggests leaving school early can have a negative impact on peoples' potential.

The federal government launched the Indigenous Advancement Strategy in 2014 as part of its Indigenous affairs budget, and streamlined funding for organisations into five categories, including education.

Indigenous Affairs Minister Nigel Scullion came under fire in March 2015, however, when he announced funding cuts to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander organisations, including youth initiatives.

Mr Scullion said less than half of the 2,345 Indigenous organisations that applied for funding under the strategy were successful.

"This government is improving the impact of Commonwealth investment in Indigenous affairs by directing effort where it is most needed to best serve our First Australians," a spokesperson for Mr Scullion told NITV after the funding was finalised.

But the National Children's Commissioner Megan Mitchell told NITV in October that Australia was better at keeping Indigenous children in detention than getting them to school.

In 2015, human rights organisation Amnesty International revealed Indigenous youth are 26 times more likely to be put behind bars than their non-Indigenous counterparts.

"That's a tragedy," Ms Mitchell said. "Because sending kids to detention is really just about sending them to criminal school."

-with Jodan Perry